The increase in the tobacco excise proposed in the 2023 Budget is very unlikely to be effective in reducing rates of smoking based on previous evidence. Instead, it appears to be a revenue grab by the Federal Government dressed up as a public health intervention. The harms caused by smoking come from both the health effects of tobacco as well as the financial burden of this addictive habit. With smoking rates in disadvantaged groups remaining stubbornly high, these populations carry an inequitable burden. The reasons for which people smoke in such groups will not be addressed by this policy. Despite an increase in tobacco tax being regressive in nature, it is widely palatable due to its link to a harmful product. However, with no public health benefit, it has no ethical justification. The public health community should not allow regressive policies to pass through unchallenged and should instead strongly advocate for policies which address inequality further upstream.

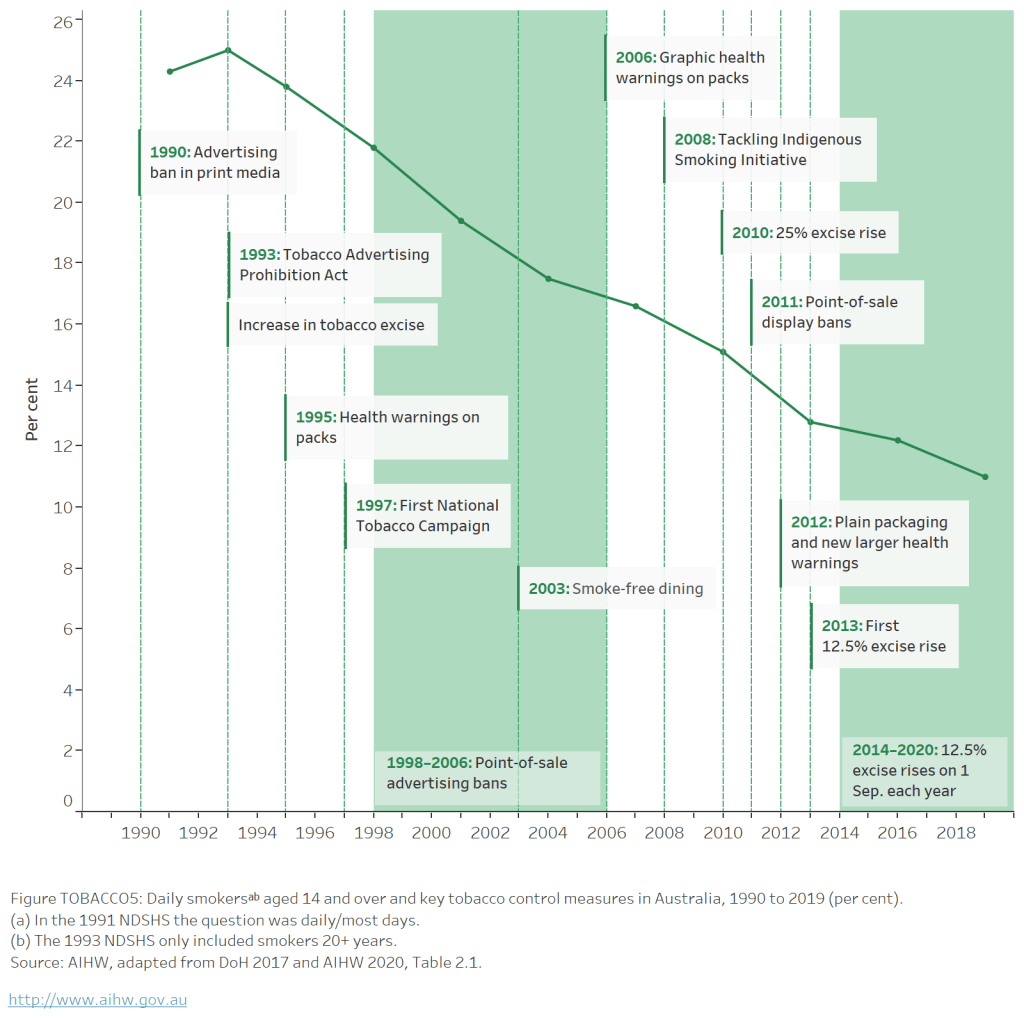

Australia has been incredibly successful in changing its culture around smoking over the past few decades. This has come about following a suite of policies including smoke-free environments, restrictions on tobacco advertising and increasing the price of tobacco through taxation. Nevertheless, smoking still contributes considerably to the country’s health burden, particularly in disadvantaged populations.

In the 2023 Federal Budget the Commonwealth Government announced another increase in the tobacco excise. The health minister Mark Butler claimed the annual 5% increase in excise over 3 years is intended to make smoking more “unattractive” while raising $3.3 billion in revenue over 5 years.

Taxes like this have two aims, to reduce demand (and consumption), and to raise revenue. But due to the high rates of smoking in disadvantaged communities, taxation of tobacco products is inherently regressive (ie the poor pay more than the rich). As a public health measure, this is particularly problematic due to the fact that the harms caused by smoking come from both the health effects of tobacco as well as the financial burden of this addictive habit. The ethical justification of the policy rests on the premise that the regressive nature of the tax is offset by the potential health benefits in groups with higher smoking rates.

However, this assumes that the policy is effective in driving down rates of smoking (ie demand elasticity), particularly in these groups. If large proportions of disadvantaged people are still smoking daily and are also paying much more to do this, is it likely for there to be a net benefit for overall health? If not, the ethical justification for the policy wouldn’t hold up.

Between 2010 and 2020, there were successive increases in the tobacco excise. In 2010, a 25% increase, then annual increases of 12.5% from 2014 to 2020. This resulted in a 200% increase in the cost of cigarettes. A pack of 25 cigarettes increased from ~$13 in 2010 to ~$40 in 2020. With such an increase in price you would expect a substantial drop in the rate of smoking, right?

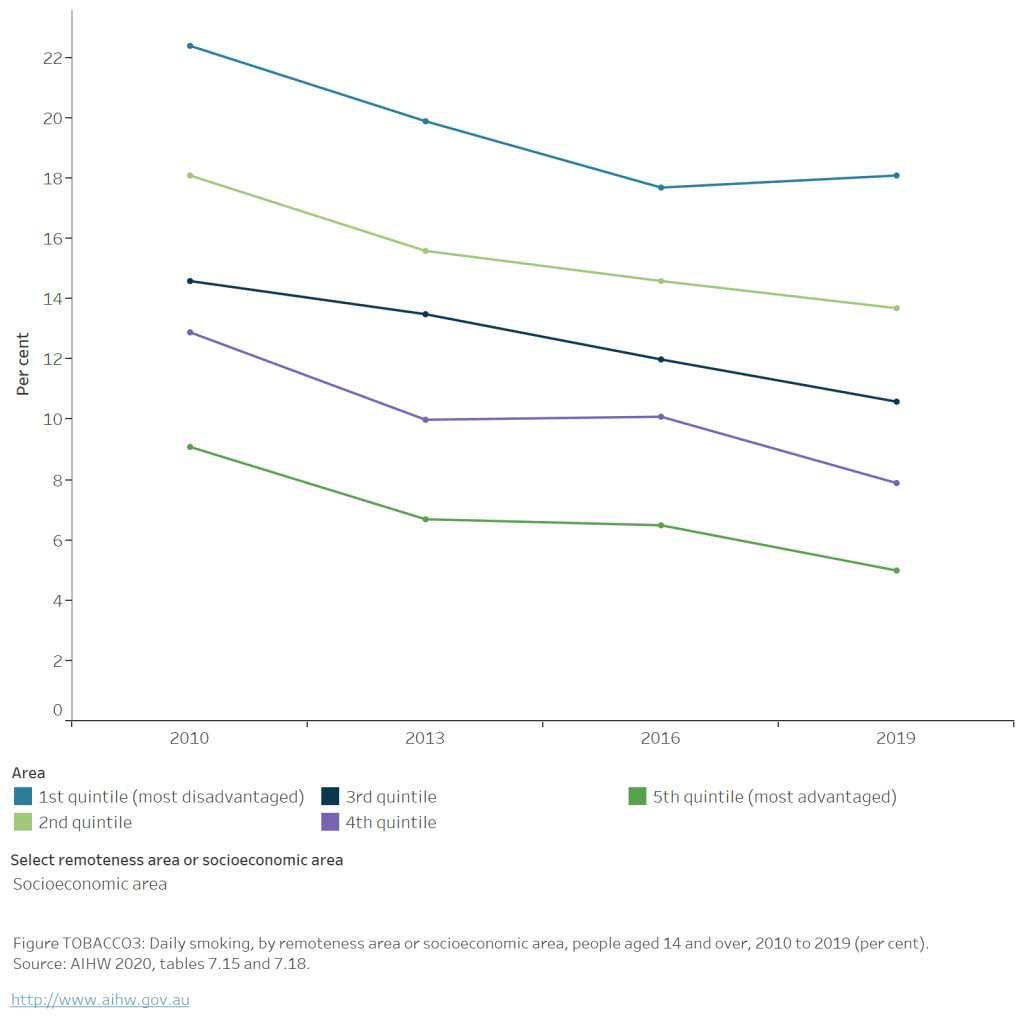

Overall, there has been a reduction in the proportion of people who smoke daily over this period. But the benefits are not substantial and are not distributed evenly. In the least disadvantaged areas in Australia, the rate of daily smokers reduced from 9% in 2010 to 5% in 2019. In the most disadvantaged areas, rates decreased from 22% to 18% in that time. So, proportionally, smoking prevalence only decreased by 18% in the most disadvantaged quintile compared with 44% in the least disadvantaged group. Between 2016 and 2019, the prevalence of daily smoking was actually unchanged in the most disadvantaged group despite a 40% increase in price in that time. So, overall, the well-off group have benefited much more from the policy than those in the poorest group.

It is possible that the amount of tobacco people consume each day has decreased in response to the increasing cost. However, this still leaves many people addicted to tobacco – including 18% of people in the most disadvantaged areas, 43% of Indigenous Australians, and 20% of people with mental health conditions who continue to smoke daily – and paying the financial and health costs.

The policy has not been successful in meeting the bar of being effective, equitable, or ethical.

Now, I’m not necessarily advocating to reduce the existing excise. But with the apparent lack of efficacy on reducing smoking prevalence of a 200% increase in total price, it’s hard to see how an annual 5% increase in the excise is going to reduce demand of tobacco – especially during a time of high inflation and cost of living. With increasing financial stress and increased prices of most everyday expenses, will a few dollars increase in the price of a pack drive someone to quit when they didn’t quit as prices rose by $30?

Given these figures, it seems extremely cynical for the government to frame this as a public health measure.

It’s clear, from the disparity in rates of smoking, that there are upstream causes of smoking which can’t be substantially modified by these kinds of proximal policies. It’s a heavily addictive substance enmeshed with our social structures. The high rates of smoking in people with mental illnesses, and in Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders further confirms this.

Poverty, disempowerment and financial stress are major determinants of health across most risk factors and diseases, including increasing the risk of smoking. If raising the tobacco excise does not substantially reduce the rate of smoking, then the financial burden it creates likely contributes to a vicious cycle, further entrenching these upstream causes. It would largely be just a punitive measure.

We need to address the upstream determinants by relieving financial and social stresses, like income and housing, as well as improving access to mental health services.

As a fiscal policy, the new tax will simply raise revenue from the most disadvantaged populations in the country at the expense of our progressive tax system – coming at the same time as tax cuts for high income earners and only meagre increases to welfare payments.

As Greg Jericho points out, the tobacco excise aims to raise more revenue than changes to the Petroleum Resource Rent Tax. Now, which of these is the more important social change?

For those calling for the funds to be earmarked for health spending, I would question using money collected from people made vulnerable by our society on measures to protect health – it seems akin to using poker machine revenue for community services.

Fiscal policy still has an important role to play in improving public health and promoting equity. Let’s focus on strengthening our progressive tax system and income support payments to meet these challenges further upstream. Let’s raise welfare payments above the poverty line and remove barriers to receiving it.

I know some will say that what I’ve argued is simply a Big Tobacco talking point. While Big Tobacco does use these arguments cynically for their own interests, this does not allow us to ignore these very important policy considerations.

In public health we sometimes see well-meaning policies being promoted which unfairly affect disadvantaged people through stigma, enforcement, disempowerment, and financial burden. It is essential that we reflect on these unintended consequences and remember that our ultimate goal is to empower people and improve their ability to enjoy their lives and participate in society.

The tobacco excise is a rare tax which is palatable to people across the political spectrum. As attitudes have changed over time, it has become easy to judge smokers and justify imposing inequitable policies on them, saying it’s for their own good. The fallacy of deterrence is intuitively attractive to the public and is convenient for legislators. However, with no ethical basis, little evidence of effectiveness, and recognising the social determinants of smoking, the excise increase shouldn’t be palatable to the public health community. It’s incumbent upon public health experts to be critical, debunk misconceptions and oppose policy which undermines the principles of equity and social justice. It’s also our responsibility to explain these nuanced issues to the public and address the stigma caused by the approach thus far.

Australian Federal and state governments, and tobacco advocates have been incredibly successful in taking on the powerful interests of Big Tobacco and changing our society for the better. Despite this, these policies have not been as effective in vulnerable groups and smoking continues to be a major issue, contributing substantially to the burden of disease. This suggests that we shouldn’t be doing more of the same.

We need to put more resources into addressing the upstream causes of disadvantage. These need to be paid for not by those who are the victims of the burden but by people who benefit from the unequal society in which we exist.